–

There’s life in the humble nation state yet

As the backlash against Brexit grows ever stronger and the Cult of Social Justice and Identity Politics eats away at our national fabric from within, there are many legitimate reasons to fear for the future of patriotism, citizenship and even the nation state itself.

However, there are also a few reasons for optimism, and Rebecca Lowe Coulson sets some of them out in Conservative Home. But first she paraphrases the question that many people are now asking about the continued relevance of the concept of citizenship:

In an increasingly globalised world, however — in which the Westphalian order of nation states is regularly criticised as inward-looking — citizenship is repeatedly denounced as an outdated representation of division and exclusion. It hardly seems necessary to comment that such denouncements typically come from the privileged, within the most economically and politically secure nations. And that, like those Britons angered at the imminent loss of their EU citizenship after Brexit, few “global citizens” seem keen to give up the privileges of their current national citizenships.

Of course, what many of those citizenship-snubbers truly want (like most of the rest of us) is for their own privileges to be extended to those living in less secure places. It is undeniable that great global imbalances remain, even though living standards continue to rise across the world. But then, the question should not be whether the concept of citizenship precludes opportunities in the sense that being a member of one state can be highly preferable to being a member of another, but whether it is still the case that one’s rights and opportunities are best protected and afforded through membership of an individuated state. In a world in which secure states increasingly offer extensive rights to non-citizen inhabitants, aCitind less secure states need more substantial upheaval and help than an improved understanding of the intricacies of membership rules, is the concept of citizenship relevant?

Coulson Lowe then goes on to explain exactly why the concept of citizenship remains relevant, and will not be undermined despite the best efforts of those who see the nation state as an obstacle to be overcome rather than a crucial guarantor of rights:

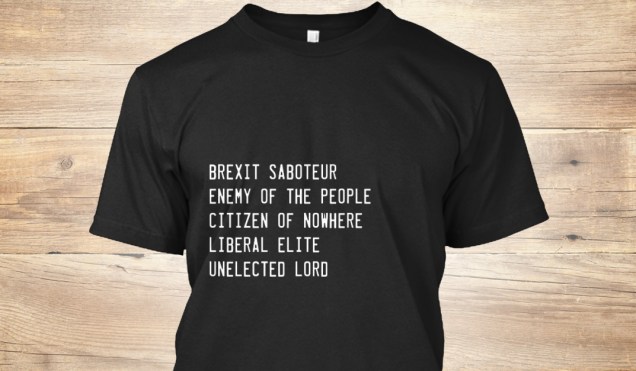

We all remember how, in her 2016 Conservative Party conference speech, Theresa May said that “citizens of the world” were “citizens of nowhere”. The comment has become symbolic of an approach for which she has been widely criticised: an approach seen both as arrogant, and as attempting to appeal to those on the further right of her party.

At the time, I felt her tone mistaken, in that I would have preferred a use of language implying greater keenness to heal, or at least address pressing divisions within the country. General criticisms of the comment often overlook the argument May was setting out, however. The words came within a section about the “spirit of citizenship”, and read, in full: “But if you believe you’re a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere. You don’t understand what the very word ‘citizen’ means”. Surely, it is that forgotten second sentence that is key, here. And that the point May was in the midst of making was about the importance of “respecting the bonds and obligations that make our society work”.

The state, and the society that exists within it, still matters profoundly to those people who aren’t happy with the countries they call home .. Official membership of such societies is conferred in different ways: from the automatic rights of familial lineage to the successful passing of a test. But the standard way of gaining the citizenship of a state is by being born and growing up in it. For those of us fortunate to count somewhere like Britain or Australia as that place, it can be easy to take for granted the relative privileges this affords us.

Yet most of us see that the uncertainties and risks of life make it expedient for us to live together in societies, and that, as social creatures, it is natural for us to want to do so, over and above that expediency. The advancements of the past centuries — in communication, travel, science, military capabilities, commerce, and on — have made it impractical for societies to remain limited to the family groups, villages, or cities they once were. The continuation of that advancement does not mean that our embrace of the nation state must also become outdated, however. For simple reasons of functionality — not to mention the more complex, such as those related to culture or national identity — it is hard to see how bigger blocs or idealist internationalist approaches could work.

This is what many on the Left fail (or are unwilling) to grasp. The Westphalian concept of statehood and sovereignty (combined with 19th century concepts of nationalism) survive the test of time because they work with the grain of human nature rather than against it. Rather than pretending against all available evidence that somebody from country A has as much in common with someone from country Z as their next door neighbour, the system of nation states is a tacit admission that the human instinct to be part of a social communities mean that harmony is best achieved when systems of government are aligned with societal boundaries. And indeed, when there is a mismatch between government and society, nation states have often split and reformed in response.

But the bigger blocs and non-state actors championed by the nation state’s detractors will not become a viable replacement in the foreseeable future, precisely because an entity’s democratic legitimacy and popular support are derived from having a demos which identifies as a cohesive whole and consents to being governed at that level.

The United States works as a country because US citizens see themselves as American first and foremost, and not Californian, Texan, Iowan, Alaskan or North Carolinian. The United Kingdom survived the 2014 Scottish Independence referendum because a majority of Scots (just about) considered themselves British as well as Scottish, if not more so.

Supranational blocs do not command this sense of loyalty or commonality among the people they nominally represent, as the European Union discovered with Brexit and will continue to discover as member states chafe against one-size-fits-all dictation from Brussels. Brexit occurred because the European Union’s drive for ever-closer union and a grander role on the world stage was plain for all to see, and the majority of voters who consider themselves more British than European wanted no part of it.

The “if you build it they will come” approach – where ideological zealots construct all the trappings of a supranational state in the hope or arrogant expectation that a common demos and sense of shared purpose will follow on automatically – has been proven to be nothing more than wishful thinking.

And this is a good thing, because as Rebecca Lowe Coulson correctly observes, supranational and non-state actors have generally proven themselves far less able to effect change than unilateral, bilateral or multilateral efforts by nation states with common purpose. The very nature of trying to shoehorn the competing national interests and priorities of multiple countries into a “common” foreign, fiscal or defence policy gives rise to resentment, suboptimal outcomes (such as stratospheric youth unemployment in Southern Europe) and inevitable net losers.

And yet the myth persists – amplified by bitter Remainers and much of the corrupted civil liberties lobby – that cooperation between countries is only possible under the umbrella of supranational government, and that these non-state actors are somehow a better guarantor of individual liberties than nation states themselves.

Take this hysterical email recently sent out by “civil liberties” organisation Liberty:

Yesterday we took another huge step towards our withdrawal from the European Union as the Government published the Repeal Bill.

If the Bill passes in its current state, people in the UK will lose rights after we leave the EU. It’s that simple and the stakes are that high.

The vote to leave the European Union was not a vote to abandon our human rights.

Yet the Repeal Bill includes worryingly broad powers for ministers to alter laws without parliamentary scrutiny and contains no guaranteed protections for human rights. Worse, it takes away the protections of the Charter of Fundamental Rights without ensuring that we will continue to protect all of those rights in the UK after Brexit.

Every single right we have now needs to stay on our statute books – from those contained in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, to equality protections we’ve gained from our membership.

Liberty – and other groups who are content for British citizens to have “rights” imposed on them from above rather than argue for and win them at a domestic level – see supranational organisations as a convenient bypass for national democracy. If the stupid British people are too dumb to vote for more employment protections and other government treats, this line of thinking goes, then advocacy groups who know better should just go over their heads to the EU. This is profoundly undemocratic, but more than that it only affirms the dangerous idea that our rights should be granted by government (at any level) rather than being innate and inalienable.

This is utterly wrong, as I explained back in 2015:

The new, emerging institutions which will replace them are being designed behind closed doors by small groups of mostly unelected people, as well as the most influential agents of all – wealthy corporations and their lobbyists. We have almost no idea, let alone influence, over what they are building together because instead of scrutinising them we spend our time arguing over the mansion tax or the NHS or high speed railways, which are mere distractions in the long run.

The liberties and freedoms we hold dear today can very easily slip away if we do not jealously guard them. By contrast, power is generally won back by the people from elites and powerful interests at a very heavy price – just consider Britain’s own history, or the American fight for independence from our Crown.

The yawning gap in the argument of those who would do away with the nation state is how they intend to preserve democracy in its absence (assuming they even care to do so). Even many of the EU’s loudest cheerleaders concede that the current institutions are profoundly undemocratic and unresponsive to popular priorities or concerns – this tends to be expressed through an exasperated “of course the EU needs reform!”, sandwiched between odes of love and loyalty to the very same entity, as we witnessed countless times during the EU referendum.

But what that reform actually looks like, nobody can say. Or at least, those few tangible visions for a future EU which do exist are so unmoored from reality as to be little more than idle curiosities – see former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis’ DiEM25, which contends both that the European Union can be persuaded to undertake meaningful reforms (ha!), and that this reformed EU should then amplify left-wing priorities to the exclusion of all others (how very democratic).

If you want to do away with the concept of the nation state or actively agitate for its demise then I think you have a responsibility to state clearly and unambiguously what you would have in its place before pushing us all into the undiscovered country. Yet the assorted citizens of the world, so anguished by Brexit, refuse to come up with an answer – at least not one which they are willing to utter in public.

The European Union is not a static entity – it is an explicitly and unapologetically political project moving relentlessly (if erratically) toward the clear goal of ever-closer union. If this is not their preferred outcome for Britain and all other nation states (and few pro-EU types will admit that this is what they want) then it is incumbent on them to offer an alternative goal with a politically viable means of achieving it.

And until they do so, the assorted enemies of the nation state do not really deserve a hearing.

–

Support Semi-Partisan Politics with a one-time or recurring donation:

–

Agree with this article? Violently disagree? Scroll down to leave a comment.

Follow Semi-Partisan Politics on Twitter, Facebook and Medium.