–

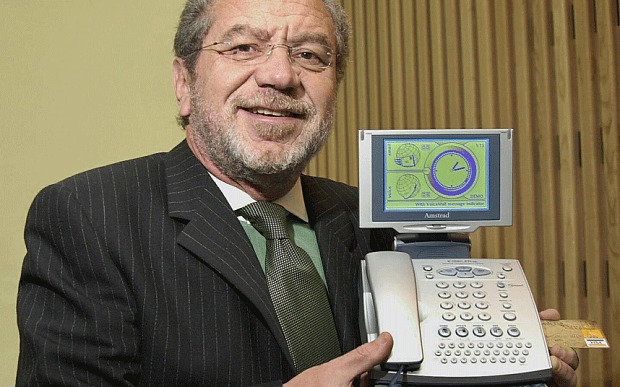

In the year 2000, when the internet was taking off and PCs and laptops were becoming more widely affordable, celebrity businessman Alan Sugar bet the house on his Amstrad Emailer device – an embarrassing, uneconomical and altogether pointless hybrid between a landline telephone and 1990s-era AOL. It didn’t go well. And now, in 2016, Britain’s facetious answer to Steve Jobs has something important to tell us about Brexit

People who host The Apprentice seem determine to shoehorn their way into our political discourse this year. First Donald Trump defeated fifteen human watercolour paintings to become the presumptive Republican Party nominee for US president, and now Trump’s British not-quite-equal, Alan Sugar, has parachuted into the middle of the raging EU referendum debate.

And Sugar certainly has Donald Trump’s ability to execute a 180 degree U-turn while vehemently denying that he has ever changed his position. Only six months ago, Lord Sugar could be found excoriating Brussels and ranting about how much the EU constrained his business. Fast-forward to today, however, and Lord Sugar 2.0 – newly appointed government enterprise tsar – is telling anyone who will listen that Britain leaving the EU is crazy and unimaginable.

From the Daily Mail:

Lord Sugar has urged voters not to be ‘daft’ by backing Brexit as he joined a host of high profile business figures who came out in favour of staying in the EU.

The businessman and Apprentice boss has produced a video making his pitch for Britain to stay in the EU.

He tells viewers they ‘could not be listening to a bigger gambler than me’ but says leaving the EU is a ‘gamble we can’t afford to take’.

Describing himself as an ‘East End chap’ who had built a business empire from scratch, he blasts the ‘daft ideas and duff proposals’ put forward by Brexit campaigners and said it would be a ‘massive mistake’ to quit the EU.

Lord Sugar, who was appointed as the Government’s enterprise tsar last week, says in the video: ‘Having lived in this country for 69 years, a country which I love, I just don’t want to see a massive mistake being made by the younger generation or, indeed, any of the generations who just simply do not understand the ramifications of leaving the European Union.’

Donald Trump would famously take any position, campaign for any cause, support any politician, donate to any political party so long as it won him access to people in power – that’s how a big Hillary Clinton supporter who was once on the liberal side of all the culture wars is now the presumptive GOP nominee. And it seems that Alan Sugar is an opportunistic sell-sword in the same vein.

But in many ways, there could be no more appropriate intervention on behalf of the Remain campaign than that now bestowed by Alan Sugar, the brains behind the Amstrad Emailer, that revolutionary and futuristic communications device. In fact, the comparisons between Sugar’s perennially unpopular “super telephone” and the European Union are quite striking.

Both the European Union and the Amstrad Emailer are anachronistic inventions, hopelessly outdated even before they saw the light of day (the EU as it is currently known came into force with the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, when globalisation was really beginning to take off and the idea of large, homogeneous regional trading blocs was already showing its age).

Like the Amstrad Emailer, the European Union takes something generally agreeable (tariff and barrier-free trade) and packages it in a fearsomely complicated design with a dozen unwanted embellishments such as all the additional trappings of a European state.

Like the Amstrad Emailer, persisting with a fundamentally flawed product in the form of the European Union reveals much about the stubbornness and contempt for democracy (the market, in Sugar’s case) held by the “founding fathers” and today’s leaders of the EU.

Like the Amstrad Emailer, nobody today would ever create the European Union as it currently exists. We only persist with it because forty years of steadily deepening political integration makes leaving a complex process and a daunting one for many – not to mention huge resistance from the establishment who like the status quo, which gives European leaders power with no accountability, and British politicians the trappings and rituals of office without the pesky responsibility.

So yes, we should welcome Lord Sugar’s intervention in the debate because the brains behind the Amstrad Emailer has inadvertently revealed an uncomfortable truth: engaging with today’s globalised, interconnected, multilateral world through the filtered lens of the EU is like trying to broadcast and receive in High Definition using one of Alan Sugar’s duff products.

For example: Norway, outside the European Union but maintaining access to the single market through EEA membership, does not delegate its voice in trade negotiations to a single EU position (itself an awkward compromise between the priorities of 28 squabbling countries).

Pete North gives a telling example of why this matters:

Not only is Norway an independent member of Codex, it even hosts the all-important Fish and Fisheries Products Committee. Thus, it is the lead nation globally in an area of significant economic importance to itself. When it comes to trade in fish and fishery product, Norway is able to guide, if not control, the agenda on standards and other matters. The EU then reacts, turning the Codex standards into Community law, which then applies to EEA countries, including Norway. But it is Norway, not the EU, which calls the shots.

Britain, meanwhile, sometimes even has to endure the indignity of seeing our own vote (on international bodies where we retain a seat) used against us by the European Commission, which controls that vote because the EU claims exclusive competency in matters relating to trade.

This is what remaining in the EU means – forsaking all of the benefits which could come from taking an active, fully-engaged position in all of the global bodies which pass down rules and standards to the European Union, and instead choosing to hide behind the EU’s skirts and accept an endless succession of fudged compromises because we lacked the confidence and skill to play the fuller role in world trade which is available to us.

Like the Amstrad Emailer, the European Union is the basic and highly predictable option, the kind of gift you might buy your grandparents (except nobody ever did) because you think that they would be overwhelmed trying to learn how to use a full PC. And now, while they could be buying things on Amazon, talking to the grandkids on Skype, blogging, editing holiday pictures in Photoshop or even setting up an online business, instead they are doomed to forever make low-quality, grainy video calls to one or other of the remaining six people in the country to own one of Alan Sugar’s devices.

That’s us. That is Britain, for so long as we remain in the European Union. A little old granny whose relatives didn’t think that she would be able to handle the complexity of a decent laptop, pecking out typo-strewn missives to the world on a rickety plastic keyboard and a monochrome screen while the richness and variety of the internet completely passes her by.

Why on earth would we vote Remain when we could vote to Leave the European Union and properly re-engage with the world as the influential, powerful and capable nation that we are? Why, when the brand new MacBook of Brexit sits wrapped with a bow on the table next to us, are we still fearfully clinging to our trusty, familiar Amstrad Emailer?

Postscript: This article in The Register provides a hilarious summary of the Emailer’s fortunes as the Next Big Thing in technology:

Since March 2000, he has tried tirelessly, and unsuccessfully, to sell the concept to everyone from journalists to politicians to the City – all have turned the device down.

Termed “the most important mass market electronic product since he kick-started Britain’s personal computer market 15 years ago” by some idiot on the Mail on Sunday, the emailer emerged in a blaze of glory at the same venue as the cheap PCs that made Amstrad a household name 20 years ago.

It cost £79.99 and still does and within a week we concluded it was far too expensive. With even low usage, it would put £150 per month on your quarterly phone bill. The public agreed with our analysis and no one bought the thing.

But the more it has failed to take off, the more fanatical Sir Sugar has got about it. He vehemently denied technical problems in August that year, then when the subsidiary set up to deal with the emailer, Amserve, put up a £2.3 million loss, he took up most of the company’s financial report explaining why the device was so wonderful.

The next set of results in February were even worse. Profit down 82 per cent from £8.2 million to £1.51 million. Again Sir Sugar waxed lyrical about how wonderful the emailer was – sales continued to be “encouraging”. This time Amserve took a £3.9 million loss.

He managed to persuade the then home secretary Jack Straw to back it up. Mr Straw said it was the perfect example of how technology could be used to “improve the flow of information and intelligence in a bid to decrease crime” at a Neighbourhood Watch photo opportunity. It made no difference to sales.

The IT correspondent for The Independent then incurred Sir Sugar’s wrath when he wrote, one year on from the launch, that the emailer had been a failure. Sir Sugar sent an email to all emailer owners, ranting about the piece and providing the journalist’s email address. Unfortunately it backfired because many of the received emails concerned the terrible problems they were having with the device.

As does this classic spoof article in The Daily Mash.

–

Agree with this article? Violently disagree? Scroll down to leave a comment.

Follow Semi-Partisan Politics on Twitter, Facebook and Medium.