The United Kingdom has fallen from 29th to 33rd in the world in the World Press Freedoms Index 2014.

The report, compiled annually by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is scrupulous in methodology and incorporates both qualitative and quantitative data. And for a country like Britain, which likes nothing more than to strut around the world proclaiming its comparative virtues, it makes for some dismal reading.

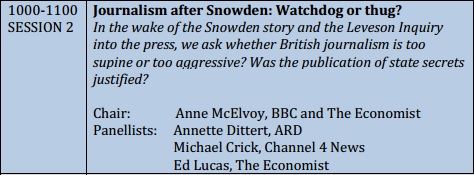

RSF’s summary of Britain is dominated by the British government’s chilling and bullying treatment of the Guardian newspaper as it sought to suppress the publication of information based on the NSA leaks by Edward Snowden, as well as the fallout from the Leveson Enquiry into the press behaviour and the prospect for further stultifying regulation of the industry:

In the United Kingdom, the government sent officials to The Guardian’s basement to supervise destruction of the newspaper’s computer hard disks containing information from whistleblower Edward Snowden about the practices of GCHQ, Britain’s signals intelligence agency. Shortly thereafter, the partner of Glenn Greenwald, the former Guardian star reporter who had worked closely with Snowden, was held at Heathrow Airport for nine hours under the Terrorism Act. By identifying journalism with terrorism with such disturbing ease, the UK authorities are following one of the most widespread practices of authoritarian regimes. Against this backdrop, civil society could only be alarmed by a Royal Charter for regulating the press. Adopted in response to the outcry about the News of the World tabloid’s scandalous phone hacking, its impact on freedom of information in the UK will be assessed in the next index.

Britain isn’t always called out by name, but there can be little doubt which European country was the intended target of this particularly barbed comment:

These developments showed that, while freedom of information has an excellent legal framework and is exercised in a relatively satisfactory manner overall in the European Union, it is put to a severe test in some member countries including those that most pride themselves on respecting civil liberties.

How true this is. Britain has long been (and has long considered itself) a stalwart defender of free speech, but the recent thuggish attempt to use anti-terrorism laws to detain a relative of a journalist and to threaten a national newspaper with closure unless it destroyed information which had the potential to embarrass the government are more worthy of Vladimir Putin’s Russia than the land of Magna Carta.

The New York Times, on the other hand, looks at the same report and seems to take succour from it, which is very surprising given the fact that their journalists have worked so closely with their beleaguered colleagues at The Guardian.

Their editorial board is celebrating the 50th anniversary of the landmark New York Times vs. Sullivan case, which set the bar for winning libel or defamation claims much higher than in Europe and thus created a bulwark protecting press freedom in the United States. This excerpt from the majority opinion in that case should be mandatory reading for all British politicians and those involved in public life, who are often all too keen to clamp down on free speech at the first sign of discord:

The Supreme Court voted unanimously to overturn that verdict. The country’s founders believed, Justice William Brennan Jr. wrote, quoting an earlier decision, “that public discussion is a political duty, and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government.” Such discussion, he added, must be “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open,” and “may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”

While the New York Times is absolutely right to recall and celebrate this landmark victory – libel laws in many other countries, especially Britain, are far too plaintiff-friendly – they seem all too willing to ignore the negative actions that have chipped away at this victory in the intervening half century, the various acts of craven self-censorship or collusion with imperial government overreach or the undermining of factfinding by the ongoing war on whistleblowers.

This selective amnesia leads to the following self-congratulatory pronouncement by the Times editorial board:

Still, American press freedoms rank among the broadest in the world. Citizens and media organizations in countries from China to India to Britain do not enjoy the same protections. In many parts of the world, journalists are censored, harassed, imprisoned and worse, simply for doing their jobs and challenging or criticizing government officials. In this area of the law, at least, the United States remains a laudable example.

The only problem with this statement? The United States ranks thirteen places behind the United Kingdom, at 46th in the world.

Fortunately for the New York Times and the reputation of the American press, the RSF world press freedom index does not take quality of journalism into account, only the ability of the journalist to practice their trade freely – otherwise they could have found themselves docked another few positions for that howler of an America-must-be-best presumption.

The truth is that neither Britain or America have anything to be proud of faced with this latest report. In an ideal world, David Cameron and Barack Obama would be held to account and hauled over the coals for presiding over such a poor performance. A backbench MP looking to bolster his or her civil liberties credentials could do worse than to ask the prime minister to defend or account for his government’s performance on press freedom at Prime Minister’s Questions this coming Wednesday.

But regrettably, a place in the mid-low 30s ranking is exactly where David Cameron, Barack Obama and many of those in power in Britain and America want their respective countries to sit. It allows for a press that is boisterous and noisy in all of the areas that don’t really matter (and so showing every outward appearance of being free), but that meekly tows the line when it comes to critical issues such as national security, civil liberties and holding those in power to account for their actions.

We in Britain or America may not think of countries such as Finland, Norway, Luxembourg or Liechtenstein as shining role models to emulate, if indeed we ever think about them at all. But in some key aspects, it is they who now carry the torch for freedom of speech and the free press, not the traditional Anglo-American partnership who held it aloft so dutifully for so long.