Well, those local council elections across England this past week were quite interesting.

The United Kingdom Independence Party has firmly established itself as Britain’s fourth (or maybe even third) party with a strong showing in which they received over 25% of the vote across those wards where they were able to field candidates.

And this despite a volley of negative and dismissive statements ahead of the elections, in which UKIP’s leadership, membership, policy positions and candidate screening processes were all mocked and derided.

Cue lots of hand-wringing about what the Tories can do to win back their disaffected supporters, etc. etc. As The Guardian reports:

A contrite David Cameron has promised to show a surging UK Independence party respect after it gained more than 130 seats in the English county elections and polled 25% of the national vote. The result led the party’s leader, Nigel Farage, to claim the birth of a new and irreversible era of four-party politics.

Cameron, who once described Ukip as fruitcakes and closet racists, admitted his mistake, saying it was no good insulting a political party that people had chosen to vote for: “We need to show respect for people who have taken the choice to support this party. And we’re going to work really hard to win them back.”

Cue also some quite entertaining journalism about the quirky, eccentric nature of British local politics. As Iain Martin writes in The Telegraph:

What is even funnier is the confusion it is causing the leaders of the established political class. They are already emerging for a round of local election bingo, with the key phrases drawn from the standard issue manual used by all the major parties. “We hear what people are saying… people want to make a protest… they want us to get on with the job… people have very real concerns… it’s mid-term… we’ll be reflecting.” But this time, when they mouth the words, they look as though they know their platitudes have been rumbled.

The distress the voter rebellion causes the bigger parties does seem to be an important part of the appeal of Ukip. Voting for Farage is an entertaining way of giving the Tories, Labour and the Lib Dems two fingers. Of course the longer-term implications are not necessarily funny. This is a country, not a comedy club. But large numbers of voters are so disenchanted that they see no possibility of an answer in the old parties. They are having a lot of fun trying to blow up the system.

Of course, this runs contrary to the counterargument that these were only local elections, that off-cycle elections always see the governing party (or parties in this case) punished at the ballot box, and that people will return to one or other of the Big Three come the general election in 2015.

But a 25% share of the vote, and a national second place position, can start to shift perceptions, a fact that Nigel Farage, UKIP’s leader, is no doubt counting on. If people absorb the consequence of these election results and no longer see UKIP as a party of “fruitcakes and closet racists”, as David Cameron once uncharitably called them, their support may not peel away as it has previously done, and we could see a number of newly minted UKIP MPs entering parliament.

But what is contained within the UKIP manifesto? Well, quirky though some of their individual members and candidates may be, the manifesto on which they are running is actually quite appealing to those who favour smaller government. The BBC offers a fair overview, which includes the following:

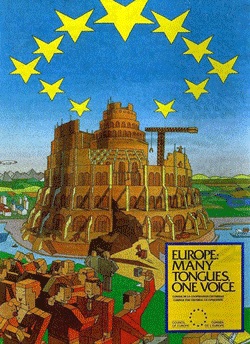

EUROPE: Nigel Farage says he wants an “amicable divorce” from the European Union. Britain would retain trading links with its European neighbours but would withdraw from treaties and end subscription payments, adopting a similar relationship with the EU to Norway or Switzerland.

TAX: UKIP favours a flat tax – a single combined rate of income tax and national insurance paid by all workers. It claims this would end the complexity of the current system and allow people to keep more of the money they have earned. It would also lead to a major shrinking of the size of the state, which would revert to a “safety net” for the poorest. The party has yet to decide the rate at which the flat tax would be levied. Its policy at the 2010 election was 31% but a recent policy paper suggested 25%. It is having an internal debate about whether there should be two rates.

EDUCATION: UKIP backs selection by ability and would encourage the creation of new grammar schools. It would give parents vouchers to spend in the state or private education sector. It also advocates the return of the student grant system to replace loans.

DEMOCRACY: The party wants binding local and national referendums on major issues.

Freedom from EU meddling and over-regulation. A fair, flat tax. Freeing the education system from those who want uniform mediocrity at the expense of individual excellence. A strong national defence. All of these are causes dear to the hearts of the small-government conservative, and make the party worthy of support.

Of course, with the good also comes the less-good:

ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE: UKIP is sceptical about the existence of man-made climate change and would scrap all subsidies for renewable energy. It would also cancel all wind farm developments. Instead, it backs the expansion of shale gas extraction, or fracking, and a mass programme of nuclear power stations.

GAY MARRIAGE: UKIP supports the concept of civil partnerships, but opposes the move to legislate for same-sex marriage, which it says risks “the grave harm of undermining the rights of Churches and Faiths to decide for themselves whom they will and will not marry”.

LAW AND ORDER: UKIP would double prison places and protect “frontline” policing to enforce “zero tolerance” of crime.

THE ECONOMY: UKIP is proposing “tens of billions” of tax cuts and had set out £77bn of cuts to public expenditure to deal with the deficit.

Anti-science climate change denial is tempered with a pragmatic approach to ensuring energy security through next generation nuclear power. The unfortunate opposition to gay marriage is at least balanced with support for civil partnerships. The spirit of cutting taxes and controlling spending is absolutely right, but the wisdom to wait until a stronger recovery exists is lacking. And the draconian, counter-productive policies on law and order are just bad.

So there is good and bad in the UKIP manifesto, just as there is in the manifestos of the other main political parties. As always, the ultimate question must be who delivers the best package of policies to improve the country?

Until now, I have been fairly dismissive of UKIP’s offering to the electorate, but no more. Here is a broadly libertarian-leaning party, offering a no-nonsense, very pro-British package of policies. And while there is a little too much authoritarianism and social conservatism still in the mix, the failings of the present Conservative-led government to revitalise the economy and enact any of the urgently-needed supply side reforms in Britain make UKIP a potentially viable alternative for my vote.

The UKIP manifesto is worth a read. Are there unsavoury fringe elements within UKIP, and endorsements from without? Certainly. Are there some rather eccentric characters representing the party at the moment, yes. Are all of the policies fully costed and backed with feasibility studies? Of course not – UKIP has never seen power, and remains a less mature political party. But then so were the Liberal Democrats until the 2010 general election gave them the chance to wield real power and become as dour and unappealing to the electorate as Labour and the Conservatives.

We currently suffer under a Conservative-led government that has done barely anything to shrink the scope and size of the state, and the meddling influence of all levels of government in our lives. UKIP promises to do differently.

And, based on their manifesto if not their fringe supporters, would that not potentially be a very good thing for the cause of smaller government and individual liberty?