–

The Oxfam sex scandal is just more depressing proof that Britain’s giant, government-funded megacharities are almost completely unregulated and accountable only to trial by media

I have refrained thus far from writing about the Oxfam prostitution/rape scandal as the fallout metastasises throughout the charity sector, but I’m sure that regular readers can already guess exactly what I think about a largely government-funded pseudo-charity staffed by overpaid mediocrities who seem to think that their primary job consists of issuing prissy, sanctimonious reports attacking the one economic system which has lifted more people out of grinding, desperate poverty than all the charities of the world put together.

Much of the counterreaction on the Left has focused on the idea that conservatives want to cynically use this scandal as a reason to discredit and cut international aid – guilty as charged, in many cases. But there is also a creeping awareness on the Left that institutionalised compassion through government-funded charities is both inefficient and politically problematic.

As Ian Dunt wrote over on politics.co.uk today:

You could feel the story bursting at the seams of its Oxfam straightjacket and trying to become one which was sector-wide, a broader indictment of charities having generally lost their way. That’s partly because there is a small army of journalists out there intent on taking on the charity sector. The Express and Mail have been obsessed for years. But that does not make it a right-wing initiative alone. Many others on the progressive left are uncomfortable with the way the sector operates.

And there have been plenty of reasons to do so. Many charitable organisations, like Oxfam, grew so big they essentially became akin to corporate giants. They started obsessing over their reputation, which can be a prologue to hushing up that which might damage it. They began paying out eyebrow-raising sums for chief execs. Mostly they could justify these sums by stressing that they wanted the best people for important missions, but that would have made little sense to many of their donors, on low incomes, who had given some of their hard-earned income on a charitable instinct, only to find that the money was funding a salary they would never come close to achieving themselves.

The government guarantee of 0.7% of GDP on aid spending, which functions as a litmus test of the Conservatives’ moral responsibility in an age of austerity, also creates perverse incentives. It reverses the process by which a government department has to justify its spending on a project. The incentive now is to find things to spend the money on. Once that happens, it won’t be long before some dubious projects get funding.

Dunt goes on to warn that if this scandal is not rapidly contained, it could become the charity sector’s equivalent of the MP’s expenses scandal, where permanent and far-reaching reputational damage is done, leading the general public to forswear making charitable donations to international aid organisations.

Dunt’s concerns – including the perverse incentives created by the pig-headed, fixed 0.7% of GDP target for international aid – are absolutely valid, and his willingness to risk angering his own side by pointing out that megacharities like Oxfam often become extensions of the clubby, incestuous Westminster bubble from where they get their funding is commendable. In fact, one wonders how Dunt can be so perceptive and forthright on this issue while simultaneously being so hysterically blinkered on the subject of Brexit, but that’s another issue for another day.

What the Oxfam scandal and other instances of gross negligence in the charitable sector teach us is that however bad corporate governance may sometimes be in the for-profit sector, it is a strict and rigorous regime compared to the unregulated, unaccountable sphere in which the megacharities and NGOs operate.

When companies like BHS or Carillion go into administration, such is the public and political outrage that people associated with the stricken company are often hauled into court to be held accountable for their failings. But when similar outrages take place in the charity sector, the public outrage may be great but the consequences for those who oversee the failings are negligible. Why? Because they were trying to “do good”, and because they come from the same social bubble occupied by many politicians and members of the judiciary. The system protects its own.

One need only think of the fawning, uncritical praise heaped on celebrity charity CEO Camila Batmanghelidjh by politicians right up until the moment she ran her charity into the ground, leaving its service users high and dry, or by the way that she was allowed to melt back into anonymity rather than face any tangible consequences for her mismanagement.

As I wrote at the time of the collapse of Kids Company:

There is an aura around certain people – and around certain professions and political stances too, one might add – which makes close scrutiny and robust criticism almost impossible. And you can hardly do better escaping scrutiny than if you happen to work for one of those favoured organisations which enjoys the favour and blessing – and ministerial veto – of senior government officials, people who are guided by the opinion polls and an all-consuming obsession with how things look over how things really are – or could be.

But when is a charity not a charity?

Here’s a clue: If your organisation receives millions of pounds from the government, and if the state eclipses private and corporate philanthropy as the main benefactor and source of income, then it is not a charity. It is a QUANGO, a Public Service In All But Name, a de facto arm of the government. It comes with all the cons of financial burden on the taxpayer with none of the transparency or oversight that government spending at least pretends to ensure.

There are hundreds of Kids Companies operating up and down the country, charities in name but in reality monopoly providers of social care and other services under exclusive contract to local councils. This broken, unaccountable model should never have come to represent British philanthropy and charitable giving.

Unfortunately, we have a habit of seeing these scandals in isolation. We rightly get worked up about Kids Company, but then the news cycle moves on and the political class have little incentive to pursue people who so frequently come from the same backgrounds and occupy the same social circles. And bad or nonexistent charitable corporate governance is allowed to continue unchecked until the media discovers the next outrage.

Ian Dunt also makes this point:

The public anger towards the political class is not restricted to MPs. It encompasses a much larger, nebulous group, from think tanks, to journalists, to lobbyists, to bankers. Charities are increasingly seen as part of that, not least because they have often adopted many of the same techniques and mannerisms. They live in the same bubble and use the same language. If it isn’t this scandal that blows apart public trust in the sector, it’ll be the next one.

Yes. Britain’s megacharities are seen as part of that larger, nebulous group because they are very much a part of it. The vast over-reliance on state funding alone means that relationship are more opaque and questionable than should be the case, while the fact that such NGOs seem to recruit heavily from the same cultural pool which fills the ranks of politicians, journalists and think-tankers mean that the public naturally (and in this case correctly) jump to certain conclusions.

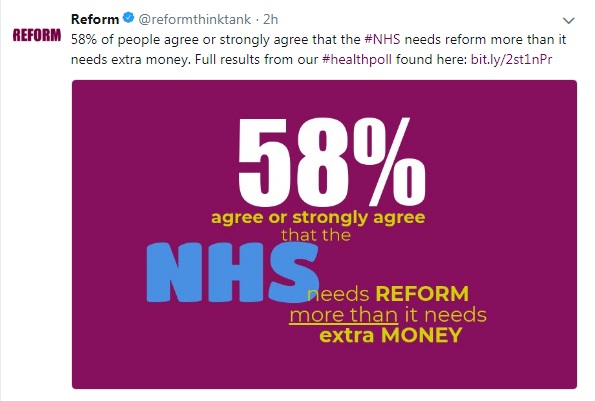

How much more generous might total British charitable donations be if they were encouraged through a tax-deduction scheme for taxpayers rather than being laundered through HM Revenue & Customs, adding to our total tax burden? And how much more efficient might out international aid efforts be if a large percentage of donations did not support support huge overheads and remuneration for senior staff?

Sadly, we are unlikely to find out. Unless we demand change or the Conservative Party finally decides to grow a backbone, Oxfam will make its insincere mea culpas, a few unfortunate scapegoats will be publicly shamed and stripped of their jobs, and the whole sleazy bandwagon will go rolling on.

–

Support Semi-Partisan Politics with a one-time or recurring donation:

–

Agree with this article? Violently disagree? Scroll down to leave a comment.

Follow Semi-Partisan Politics on Twitter, Facebook and Medium.