If your country faced annihilation by a foreign army, would you take up arms in its defence? Many would, and many have throughout our history – this year we honour the memory of the six million British men who fought in the First World War, many making the ultimate sacrifice for King and country.

But if your country was days away from a seemingly more banal kind of destruction – at the ballot box, following a largely dull and petty referendum campaign – what would you say to save it?

The Spectator has issued this challenge to its readers, asking them to submit letters to a wavering Scottish voter, imploring them to choose to remain in the Union. Entrants have complete freedom to say what they like within this broad remit:

You can make only one point, or make a bunch of them. The letter can be funny or deadly serious, clinically rational or a cri de coeur. The aim is to show that people in certain parts of Britain do care, very much, about the other parts – and that the Britishness which binds us together is worth fighting for.

The timing could not be better: a shocking new poll has given the “Yes” to independence campaign the lead for the first time, with 51% of respondents in favour of ripping up the Act of Union, and 49% preferring to maintain the bonds that tie us together. The Better Together camp long predicted that the polls would tighten as the referendum neared, but this latest poll is an absolute calamity, almost guaranteed to sew the seeds for further infighting and recrimination among unionists.

Immediately I got to work. I would gladly participate, I would find that elusive combination of words that would make Scottish independence supporters come to their senses and see reason. Where countless celebrities, politicians and statesmen had failed, I would succeed.

Four drafts later and I have nothing.

As a political writer and blogger I should be full of excitement and opinions about the latest opinion poll, and spend my time analysing the implications and wondering how each side will respond now that their fortune have apparently flipped. The Spectator’s Isabel Hardman does a typically fine job of this:

The question is who will this poll galvanise the most? Will it horrify wavering voters and send the Better Together campaign into a final frenzy to win over those lingering undecideds? One thing we can be certain of is more detail on what further powers Scotland would get if it stayed within the UK. Or will it give the SNP a final furlong spurt of energy? As we’re dealing with an expected turnout of around 80 per cent with voters who have never pushed a slip of paper into a ballot box before coming out to vote, no-one knows the answer. And that’s what makes tonight’s poll particularly terrifying for unionists.

I suppose I should also take the lead from many senior unionist politicians and pundits, and be ready and willing to say anything, do anything and offer anything by way of bribery or cajolement to convince wavering Scots of the readily apparent benefits of our United Kingdom. But I cannot engage in this flattery, just as I cannot engage in tactical speculation and analysis on this subject any more. The threat is too great and the imminent pain too real to treat the prospect of the end of the United Kingdom as just another political football.

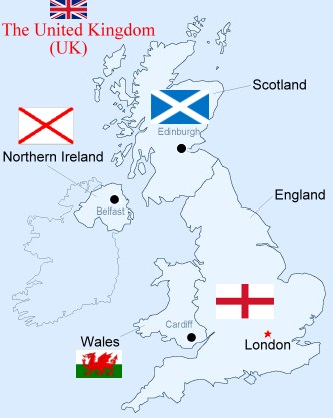

I have written at length about my belief that our great country should remain united, and that we should not seek to create ever-smaller subdivisions on our small, crowded islands (though I strongly favour a federal United Kingdom). I have talked about the constitutional issues that would arise, and the fact that bespoke pandering to Scottish nationalists at the expense of the English, Welsh and Northern Irish is further unbalancing our constitution. I’ve argued in support of continuity for what has been proven to work in preference to an unresearched leap into the dark.

But at this point I have nothing left to say, not even 250 words. Not even in the face of the depressing news that Gordon Brown is to become the figurehead for the “No” campaign, further cementing the desperate idea that left wing bribes are all that wavering Scots want to hear.

If the Scottish people search their collective hearts and decide to destroy the United Kingdom in a bid for complete self-governance with no remaining ties to England, Wales and Northern Ireland, they should go. The UK will not be worth saving, because we will have forgotten who we are. We can await our diminished future as the fifty-first (and second poorest) state of America, or our balkanisation into soulless geographical regions by the European Union.

I watched the two awful televised debates between Alex Salmond and Alistair Darling. I watched as the Better Together camp made the ludicrous, doomed decision to compete with the SNP in devotion to left-wing, big government principles. I watched as the Yes camp peddled their denialist fantasy in which an independent Scotland walks away from its share of the national debt, uses the pound while influencing UK monetary policy in it favour, accedes immediately to European Union membership and funds its socialist utopia with limitless oil revenues from the North Sea.

How does one engage in a debate when one side argues for what should not be and the other side clamours for something that cannot possibly be?

The Better Together side’s latest grand idea is talking up the prospect of David Cameron being defeated in the 2015 general election, and holding out the prospect of a more appealing, left-wing alternative in Ed Miliband. But must we really now start to base our national identity according to the same brittle rationale by which we choose our newspaper habits and prune our social media feeds, seeking to insulate ourselves from contrary opinions and perspectives, and identifying only with those people who agree with us politically?

This is the toxic, petty world inhabited by the likes of George Monbiot, who believes that a Scottish “No” vote would be an “astonishing act of self-harm”:

What would you say about a country that exchanged an economy based on enterprise and distribution for one based on speculation and rent? That chose obeisance to a government that spies on its own citizens, uses the planet as its dustbin, governs on behalf of a transnational elite that owes loyalty to no nation, cedes public services to corporations,forces terminally ill people to work and can’t be trusted with a box of fireworks, let alone a fleet of nuclear submarines? You would conclude that it had lost its senses.

There is no point attempting to reason with the likes of Monbiot, a man so determined to see evil in everything the United Kingdom stands for and so willing to buy the Scottish nationalist snake oil. But there may yet be time to prevail upon those Scots who are not so embittered by the mere thought of capitalism, private enterprise and a strong nation state as our best model for human governance.

At a time when people from the four home nations of the United Kingdom sometimes look at each other and see no common bond left, we would do well to remember the example of our former colonies in the New World. Each of the fifty United States of America boasts its own distinct culture, accomplishments and economic strengths. Each fancies itself the greatest state in the union. But when push comes to shove, almost everyone in that great land proudly considers themselves to be an American – even if, in the case of the Lone Star State, they may call themselves Texan first and foremost.

An American born and raised in Kansas may never set foot in the state of California, but they would be rendered incomplete if the land of pacific beaches, the Golden Gate Bridge and the great Redwood forests were to wrench itself away and start governing itself for the benefit of Californians alone. Those in the American heartland may be different from their coastal cousins in as many ways as you can imagine – taste in food, fashion, approach to religion, views on social issues and love of firearms – but they share the same historical bond, forged in war and peace, that Scots share with the English (and Welsh, and Northern Irish) whether they like it or not.

I have no words of my own left to flatter or bribe my wavering Scottish cousins into preserving something so precious and yet apparently so undervalued north of the border. I can’t participate in the ideological race to the left, nor do I think framing the debate as a competition to promise Scots the most left-wing gimmicks is in any way helpful or illuminating. I can only offer the words of another, a great man who rose to the occasion when his country seemed destined to tear apart at the seams.

At his inauguration in 1861 and on the eve of the American civil war, President Abraham Lincoln reasoned and pleaded with the restive Southern states, seven of which had already declared their secession from the Union, in this way:

That there are persons in one section or another who seek to destroy the Union at all events and are glad of any pretext to do it I will neither affirm nor deny; but if there be such, I need address no word to them. To those, however, who really love the Union may I not speak?

Before entering upon so grave a matter as the destruction of our national fabric, with all its benefits, its memories, and its hopes, would it not be wise to ascertain precisely why we do it? Will you hazard so desperate a step while there is any possibility that any portion of the ills you fly from have no real existence? Will you, while the certain ills you fly to are greater than all the real ones you fly from, will you risk the commission of so fearful a mistake?

And as Lincoln said in closing to the rebellious American South, I can only repeat to the United Kingdom’s restless north:

I am loth to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.