–

What does it mean to be a dual citizen in the Age of Brexit?

Following my recent blog post lamenting our society’s devalued and transactional concept of citizenship in the Age of Brexit, I was asked by a reader to write a companion piece on the topic of dual citizenship, a form of recourse which may ultimately be taken up by many EU residents currently living in Britain.

The request was as follows:

Brexit has caused (we are told) applications for passports from people who already hold passports – that is, people who are citizens of one European country seeking to become a citizen of a second country too.

This apparently includes UK citizens applying for Irish passports (without abandoning their UK passports) and people from continental countries who live in Britain applying for a British passport too (presumably this means going through the naturalisation process?). One wonders how many people who announce that they are planning to do it actually do – but it is evidently happening.

It is questionable why people should be able to be dual citizens if they live in democracies and are free to travel and work abroad. The ability to claim benefits in a second country seems to be one impetus. But it can cause people costs, like two tax liabilities. Some countries do not allow their citizens to take another citizenship without renouncing their existing one, but there seem to be many countries which are happy to agree to dual citizenship.

Your article of 12 September explains well how citizenship is becoming a sort of transaction – benefits for taxes, and no longer an allegiance to a nation. The large increase in people obtaining (why not triple?) citizenship could further undermine the significance and value of being a citizen of a country.

My reader seems to build on my assertion that citizenship is increasingly seen (particularly by educated, globally mobile elites) as very much a transactional affair with perks received in exchange for taxes paid, and extrapolates that dual citizenship is necessarily a further dilution of the bond between citizen and nation state.

This is a tricky subject for me to discuss, primarily because I will ultimately be emigrating to the United States with my Texan wife (who is herself currently in the process of applying for British citizenship). Therefore, to rail against the concept of dual citizenship would be hypocritical, while approving too strongly might be seen as merely attempting to justify my own personal circumstances. All I can do when setting out my views, therefore, is to make people aware of this potential bias and lay out my thinking on the matter as it currently stands.

In short, I do not believe that dual citizenship is either inherently good or inherently bad. Though there is undoubtedly a correlation between those who hold dual citizenship and the kind of fleet-footed “Citizens of the World” who feel that they have transcended national identity altogether, it is perfectly possible in my mind for somebody who holds dual citizenship to be a model citizen of both countries, while somebody without an international lifestyle can just as easily be a terrible citizen of the only country they call home.

Therefore, I don’t think it is a question of whether dual citizenship as a concept is right or wrong. The more interesting question to me is what makes somebody a good citizen of their home or adopted country, and what makes somebody a bad or negligent citizen.

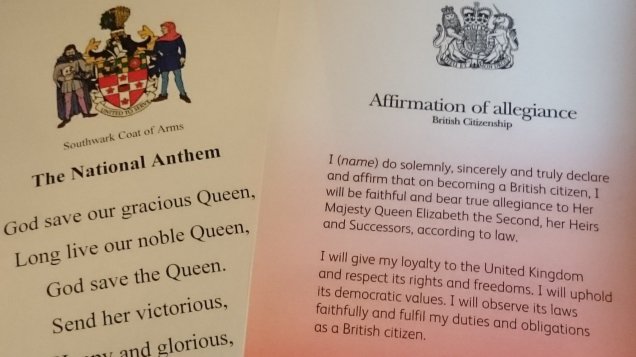

One could probably define this a thousand different ways, but for immigrants seeking to naturalise as dual citizens surely it includes a mixture of more tangible qualities (being economically active, law-abiding, involved in the community) and intangible qualities (genuine interest in and acceptance of the country’s culture and values). Immigration authorities typically only look at the tangible aspects – what else could they do? – but while this scrutiny can reveal whether somebody is likely to be an economic burden or a danger to society, it is the intangible (and largely immeasurable) qualities which really determine whether or not somebody will make a good citizen.

From my own experience, I have loved the idea of America since I was an early teenager, and the reality of America just as much, ever since first experiencing the country in my late teens. The architecture, the art, the (classical) music, the landscape and the sheer optimism of America captivated me well before I was politically aware, and the Constitution, federal system and that strange but compelling contradiction between individualism and great community-mindedness equally appealed to me as I came to understand them.

America is a country that I feel I know well. Not just in the sense that frequent holidaymakers might be able to direct somebody to their favourite restaurant in New York City, or the way that US-based foreign correspondents come to know the political and cultural elites with whom they rub shoulders, but at a much deeper level.

I have visited and worked in towns and cities across that great land, from New York to Chicago to Kansas City to Austin to San Antonio to Seattle, and many smaller places in between. I have seen and savoured some of the best of urban and rural living in America, from hearing the New York Philharmonic play John Adams, riding a stranger’s horse in Colorado and experiencing the Catholic Mass with Mariachi music in my wife’s south Texas hometown to eating fried food on sticks at the Illinois State Fair. I have spoken with people from the most left-leaning liberals to the strictest social conservatives and found nearly everyone to be unfailingly polite and welcoming – though a couple of men I once conversed with at a hotel bar in Arkansas were none to happy that America had a black president (they used a different word).

I have seen (some of) the best of America, and glimpsed the darker side, too. And so when the day finally comes that I raise my hand and take the oath of allegiance to the Constitution and laws of the United States of America I will be aligning myself with a country that I know and love, for all its greatness and its imperfections.

I will not become an American to join a closed community of fellow British expats, clustered together in one locale and unwilling to integrate with American society. I will not become an American to try to make the United States more like Britain. I will not become an American because the taxes are lower (though they are), or because I think I can get more from the welfare system (I certainly won’t). I will not become an American merely because the United States is a temporary work posting, a brief stopover as part of a transnational career. No, I will become an American because I will one day make that place my home and want to share that bond of citizenship and fraternity with my fellow citizens; because I want to participate in American democracy and every facet of civic life open to citizens.

But even as I do so, I will not lose affection for the United Kingdom, my homeland. I will remain connected to Britain not only through ties of family and friends, but because I am proud to be British and have been an engaged citizen of this country for so long, politically and culturally. When my wife and I have children we may well want them to spend some years growing up in London so that they know the rich culture that is also their inheritance. Far be it from me to brag about myself, but as an abstract ideal for the model dual citizen this would seem like a decent enough template.

But the diluting effect of loyalties mentioned by my reader is undoubtedly a real phenomenon. I would think it highly unlikely that anybody could maintain such strong connections as the number of countries and citizenships involved ticks upward. I have to tread carefully here, because I have a number of dear and longstanding friends who hold multiple citizenships, and uncontestably have strong attachments to and affection for each country in question. One cannot make judgments about individuals from population trends, or infer population trends from observing individuals, but at a macro level I think it is generally the case that deep attachment to a nation state decreases as the number of citizenships in play increases.

The degree to which the cultures in question differ from one another probably also determines whether it is possible to form a deep bond to multiple countries. I would imagine that growing up in a Middle Eastern theocracy would make it at least somewhat harder to form deep bonds of attachment to a country with Western values and culture while maintaining undiminished affection and loyalty to one’s homeland, though there are undoubtedly many such dual citizens who do not experience (or at least overcame) any cognitive dissonance in this regard.

Many residents holding a particularly high number of citizenships are likely to have acquired at least one from birth or through their parents, and may have very little connection to the culture of that country if they grew up without living there. I know several people who hold Spanish citizenship through birth, though the closest connection they have with Spain is having occasionally vacationed there as a child. Does this make them bad citizens? I wouldn’t necessarily say so, since their citizenship is passive – they do not live in Spain or participate in Spain’s democratic process, and so their effect on Spain is neither positive or negative.

And of course there are particularly mobile members of the economic elite who often tend to have more in common with elites from other developed countries than with their less affluent neighbours. Benjamin Schwarz is the latest to pick up on this particular trend, over at The American Conservative:

Reflecting and exacerbating the cultural divide, these cities have increasingly become culturally homogenous echo-chambers. The consumption patterns and cultural and political attitudes of, say, London, central Paris, the westside of Los Angeles, the northside of Chicago, Manhattan, Seattle, Northwest D.C., Toronto, and San Francisco resemble each other more than they do their outlying districts and suburbs.

As befits these engines of global capitalism, these cities and their inhabitants are pulling away with growing momentum from their native countries and cultures. Untethered from their localities, they are being transformed into an archipelago of analogous islands.

Again, does this mean that a well-travelled, prosperous knowledge worker with an international career cannot be a good and conscientious member of his or her community and country? Of course not. But it seems highly likely that people who are rooted Somewhere will have a greater sense of belonging and loyalty to their country than people who are rooted Anywhere. This is not intended as a moral judgment, but simply a statement of probability.

This hypothesis was proved in the EU referendum, where the vast majority of the foreign-born Anywheres living in Britain were strongly for remaining in the European Union and dumbfounded to the point of trauma at the vote for Brexit. For example, many Americans living in London simply couldn’t understand why Britain would want to secede from a supranational political union in the name of nation state democracy, even though their own country would never in a million years submit to the same kind of incursions on sovereignty inflicted by the European Union. In this regard at least they clearly have more in common with the transnational elite than the majority of citizens of their own country (or Britain, as it turns out).

In all of this, I feel like something of an outsider. I have enjoyed an international career myself, will one day be a dual citizen and in most ways am very much part of the “elite” that I spend an increasing amount of time thinking and writing about. My wife and I live in West Hampstead, an area of London which voted overwhelmingly for Remain in the referendum, and in which French is probably the second-most common language heard on the high street. We have become snobs about good coffee, visit food trucks on the weekend and (God help us) occasionally shop at Whole Foods.

Yet I am not at one with the hive mind of my demographic, which leans strongly toward the pro-European, trendy Left. I don’t think that this makes me any better or worse than people who hold the prevailing views of my social circle, but whether by the circumstances of my childhood or some quirk of the brain I do seem to be able to empathise with those who fall outside my demographic or otherwise think differently. I see the condescending, insular selfishness of the centre-leftist metropolitan worldview even as I personally benefit from many of the resulting policies.

This is probably why my stance on dual citizenship is nuanced to the point of sounding tortured. But since the ability to empathise with people of all circumstances is to my mind an essential part of being a good citizen, to this extent I do consider myself a better citizen (though by no means a better person) than those who hold the typical pro-EU, metro-leftist worldview.

Personally, I feel rooted emotionally and circumstantially to only two countries – Britain and America. There are other countries which I know well, love and respect. I have enormous affection for France, from the scruffy Pas-de-Calais to the trendy Marais district of Paris. I know and like the French culture and character. But I do not feel French, nor would I, even if I were to take a job in France for a number of years. If I were ever to take French citizenship it would only be the result of a need to formally codify my status there for administrative reasons, or because I wanted to participate in the democracy of my host nation. It would very much be the more transactional approach to citizenship that my reader decries. By contrast, I already feel part-American – the only thing which lags behind is the paperwork.

Others may enjoy the rare ability to feel real, abiding love for multiple countries, to hold six or seven passports and be willing to fight and die for each represented flag, if necessary. I am not one of those people, and as a tenuous member of the so-called elite I can report that very few of them cross my path. Therefore I think it almost self-evident that there is a negative correlation between citizenships held and deep attachment to each – but it is a trend with many many outliers, and one cannot prejudge anybody based on this factor alone.

So is it possible for dual citizens to be good citizens of both countries? Yes, of course – or at least I hope so, for my sake. But the qualities that make a good citizen cannot be measured or screened for during the immigration and naturalisation process (even attempting to do so would veer into draconian thought-policing of the worst kind), and so we are left struggling to promote the concept of citizenship to a group of people many of whom have lost faith in the very concept. But just as one hopes that people take the institution of marriage seriously while simultaneously recognising that many people will not do so, so one must accept that some people will become citizens of a new country thinking only of the benefits and not the obligations.

At present, many of those who oppose Brexit – both British citizens and EU residents – declare themselves “Citizens of the World”, meaningless phrase though it is, as a way of signifying their disdain for what they see as an insular and parochial worldview.

But as I wrote last year:

In my experience, self-described citizens of the world have tended to describe their outlook in terms of what they get from the bargain rather than what they contribute in return. They call themselves citizens if the world because being so affords them opportunities and privileges – the chance to travel, network and do business. Very few people speak of being citizens of the world because of what they give back in terms of charity, cultural richness or human knowledge, yet all of the people that I would consider to have been true citizens of the world – people like Leonard Bernstein or Ernest Hemingway – fall into this latter, rarer category.

If the former, more parasitic attitude is what comes to represent dual citizenship then I have no desire to be associated with it. But it need not be like this. Dual citizens can be among the very best citizens of a country, holding a deep appreciation for their new home that many natural born citizens lack or take for granted, while also bringing with them the best values and traditions of their homelands.

And these people we should welcome with wide-open arms.

–

Support Semi-Partisan Politics with a one-time or recurring donation:

–

Agree with this article? Violently disagree? Scroll down to leave a comment.

Follow Semi-Partisan Politics on Twitter, Facebook and Medium.